Saggi

Reflections on Leopardi, Borges, Deleuze and the Rhizome

Paola Cori

University of Birmingham

paola.cori@gmail.com

The reason I have decided to place Leopardi alongside Borges and Deleuze is because they all share a theoretical interest in, and a concern with, the linear model of time based on the principles of succession and the infinite divisibility of temporal fragments. Moreover, in order to overcome the intellectual problems posed by linearity and divisibility they all use rhizomatic models. Of course it would not have been possible for Leopardi to propose alternative theories to linearity, as Borges did with the model of parallel universes and the theory of forks in time, which derive from post-Einsteinian physics, but I would nevertheless like to show that certain features proper to these theories are also present in Leopardi, not in theoretical terms, but in a performative sense, in the practice of writing and reading the Zibaldone.

After showing the kind of concern with the divisibility of time that Leopardi and Borges share, I intend to introduce the characteristics of the rhizome theory by Deleuze-Guattari and to verify whether and how far a rhizomatic model of memory operates in Borges’ Funes the Memorious (1942) and in Leopardi’s Zibaldone.1 Whilst for Borges I will examine the way memory appears as a topic and content of his narrative, for Leopardi I will not focus on the content of specific speculations but rather on the general structure of the Zibaldone and on the way Leopardi performs the dialectic between the fragment and the whole as a writer and a reader.

Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise which Borges discusses in the essay The Perpetual Race of Achilles and the Tortoise (1929, TL: 43-47) neatly demonstrates the problem of divisibility. According to the paradox, Achilles tries to catch up with the tortoise, who has been given a ten-meter head start. Achilles runs ten times faster than the tortoise, and runs those ten meters, while the tortoise runs one; Achilles runs that meter, the tortoise runs a centimetre; Achilles runs that centimetre, the tortoise runs a millimetre and so on, so that the margin between them becomes infinitesimally smaller without Achilles ever catching the tortoise. Even though common sense dictates that if the race really took place, it would not take long for Achilles to overtake the tortoise, in Borges’ opinion,

The paradox [...] is an attempt upon not only the reality of space but the more invulnerable and sheer reality of time. I might add that existence in a physical body, immobile permanence, the flow of an afternoon in life, are challenged by such an adventure. Such deconstruction by means of only one word infinite [...], once it besets our thinking, explodes and annihilates it. [...] Zeno is incontestable, unless we admit the ideality of space and time (TL: 47).

Meditation on the divisibility of time results in an awareness of the hallucination of our existence. Indeed, our way of relating to reality is based on the intellectual understanding of linear succession, while our sensorial perception, which often experiences time as flux and also experiences the sameness of certain recurrent moments, denies succession. As Borges outlines in his essays A New Refutation of Time (1944, A-1946-’47, B, TL: 317-332) and in A History of Eternity (1936, TL: 123-139), it is possible to experience a sense of sameness between a past and a present moment which contracts the years into a sense of eternity, into the feeling that time has never passed. When this happens the concept of time as duration loses its meaning, because the intervals between the two moments fall away completely. The problem is that our impression contrasts with the rational awareness that time exists and that it is made of successive intervals. As Borges puts it:«Life is too impoverished not to be immortal. But we lack even the certainty of our own poverty, given that time, which is easily refutable by the senses, is not so easily refuted by the intellect, from whose essence the concept of succession appears inseparable» (TL: 47).

In the article Three Versions of Divisibility, William Egginton compares Borges’ (and Kant’s) meditation on time with the discoveries of contemporary physics, and shows that the concept of the ideality of time and space to which Borges refers resembles the conclusions of contemporary science. Theories on black holes have demonstrated that the space unit of Planck’s square is the limit before which space can be divisible and still preserve the characteristics of space — which are related to the single unit of entropy they carry.

«Nevertheless», writes Egginton, «this would not imply that more fundamental and “smaller” processes were not at work; instead, the idea is that whatever “underlies” space and time is not itself conceivable in spatiotemporal terms. The real, whatever it is, is not of the same substance as space and time» (Egginton, 2009: 63), and therefore the problem becomes that of observation. We, as observers, inhabit the categories of space and time, but there are certain phenomena which are at the origin of what we call reality, which do not belong to these categories and cannot be pictured in the mind.

Leopardi was also aware of how our perceptions are based on the discrepancy between how we perceive things and how things are in themselves. Indeed, in the Zibaldone entry 1160, he writes that:

non si dà cosa veramente e assolutamente indivisibile, ma se considereremo le opere dell’uomo o di qualunque agente, vedremo che alcune ci si presentano come indivisibili, e non continuate, altre come divisibili e continuate.

[There are no truly and absolutely divisible things, but if we consider the deeds of human beings or of any other agent beings, we realize that some things present themselves as indivisible and not continuous to our eyes, others as divisible and continuous.]

This discreteness, or divisibility, is the pre-condition for our understanding and for our intellect to function. Our mind, Leopardi believes, can only grasp and retain what is determined and clearly framed. Our thought can extend only to the limits of matter, and where there is matter there is divisibility. If we could find something indivisible, then we would have to admit that beyond this unity there is something that is in antithesis to what we know as and call existence, an antithesis to being which is nothingness, and which our intellect cannot approach.2 Given that we cannot describe or grasp an instant of time in its infinite smallness, to refer to the present we need to enlarge it somehow, to depict it as something different from what it is. In the Zibaldone entry 3265 Leopardi observes that:

Niun pensiero del bambino appena nato ha relazione al futuro, se non considerando come futuro l’istante che dee succedere al presente momento, perocchè il presente non è in verità che istantaneo, e fuori di un solo istante, il tempo è sempre e tutto o passato o futuro. Ma considerando il presente e il futuro non esattamente e matematicamente, ma in modo largo, secondo che noi siamo soliti di concepirlo e chiamarlo, si dee dire che il bambino non pensa che al presente.

[None of the thoughts of the new born baby is related to the future, unless we consider as future the instant succeeding the present moment, because in reality the present is only instantaneous, and apart from one instant only, time is always and entirely either past or future. But if we consider the present and the future broadly and without mathematical precision, as we are accustomed to doing, we should say that the baby only thinks in the present.]

In the Zibaldone entry 3510, when referring to the divisibility and measurability of time, the situation described by Leopardi is reversed: even admitting by hypothesis that we can consider reliable the tools which allow us to calculate the intervals of time, which is again a premise arising from the perspective of the observer and not part of the reality of time, the problem here is that the objective calculation does not match the inner feeling of time, which brings us to perceive the inner experience, or in other words its divisibility, in a more or less contracted way.

It is evident that Leopardi is aware of the gap which separates the perceiving subject from the reality perceived and of the fact that we, as observers, can only produce an approximate evaluation of time which does not correspond to its essence. We can only consider the present broadly, and measure our action in a system of conventional spatial and temporal coordinates, which are useful but unreliable from an epistemological point of view.

Moving to Borges, Funes the Memorious centres on a dialogue, presented through indirect discourse, between Borges the narrator and the character Ireneo Funes. It revolves around the topic of the excess of remembering, and builds on the opposition between singularities remembered and visualized to an extreme degree, and a kind of generalization which implies forgetting. As a result of an injury sustained by falling from his horse, Ireneo Funes develops an incredible capacity to remember every detail of past experiences as well as all the sensorial perceptions which accompanied them. The narrator describes Funes’ infallible memory in the following terms:

we in a glance perceive three wine glasses on the table; Funes saw all the shoots, clusters, and grapes of the vine. He remembered the shape of the clouds in the south at dawn on the 30th of April of 1882, and he could compare them in his recollection with the marbled grain in the design of a leather-bound book which he had seen only once, and with the lines in the spray which an oar raised in the Rio Negro on the eve of the battle of the Quebracho [...]. He told me: I have more memories in myself alone than all men have had since the world was a world. And again: My dreams are like your vigils. [...] My memory, sir, is like a garbage disposal (FM: 112).

For Funes memory is merely storage and all the parts and perceptions which constitute a single memory are constantly displayed as separate points on a surface which he sees contemporaneously. We could imagine Funes’ mind as a horizontal plane where each memory is broken into an infinite number of details, without being connected to any other memories. Funes knows the exact moment when these images and perceptions were originally produced in the mind, so these isolated memories derive from the projection of moments in time into a fragmented mental plane, whose components are forever fixed in their positions. Funes does not remember through the association of ideas, but only by providing each single perception with its exact temporal origin in the past.

This is why the narrator states that Funes was

almost incapable of general, Platonic ideas. It was not only difficult for him to understand that the generic term dog embraced so many unlike specimens of different sizes and different forms; he was disturbed by the fact that a dog at three-fourteen (seen in profile) should have the same name as the dog at three-fifteen (seen from the front). He was the solitary and lucid spectator of a multiform world which was instantaneously and almost intolerably exact (FM: 114).

Borges’ attitude upon remembering is exactly the opposite of Funes’. Knowing that «we all live by leaving behind» (FM: 113), he believes that Funes was incapable of thinking because «to think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract» (FM: 115). It is significant that Borges decides to narrate the story through free indirect speech rather than direct discourse, thus offering a synthesis that sacrifices details.

Borges creates an alternative to the linearity of time and to sequential succession through the theory of forking paths. According to this theory time exist in both a virtual and a solidified form. The virtual state of time is constituted by a labyrinth of infinite temporal pathways. Each of them forks and actualizes in two different contradictory presents. Given that the paths are infinite and that therefore the outcomes are infinite, there are infinite possible combinations: some are contradictory and will therefore never constitute a line of time, but others are compatible and able to emerge as a solid form of time. In this model, where the labyrinth is always «in a process of becoming a line» (Martin-Jones, 2006: 24), the problem posed by Zeno’s paradox, which is to explain how time can proceed over discreteness, is overcome: indeed in the forking paths a present moment is not derived from one single past moment only, in a relation of cause and effect, but each moment might be the result of many different pasts which followed different paths and intersections.

Becoming is not only at the core of Borges’ concept of forking time but also the fundamental principle of a more general system of knowledge, the rhizome, which Deleuze elaborated with Guattari. The theory of rhizome proposes a model of knowledge and of the written text as an assemblage, as a multiplicity of discrete elements involved in a system of lateral connections and anti-hierarchical relations. According to Deleuze and Guattari, the rhizome is essentially a map «entirely oriented toward [...] experimentation [...] open and connectable in all of its dimensions; it is detachable, reversible, susceptible to constant modification». It also «has multiple entryways» and «it has to do with performance» (Deleuze-Guattari, 1996: 12). We could say that Funes exhibits certain characteristics of the rhizome through the multiplicity of his memories and the fact that they are all of equal status because of his inability to prioritise them, yet his memory lacks the fundamental rhizomatic principle of connectivity.

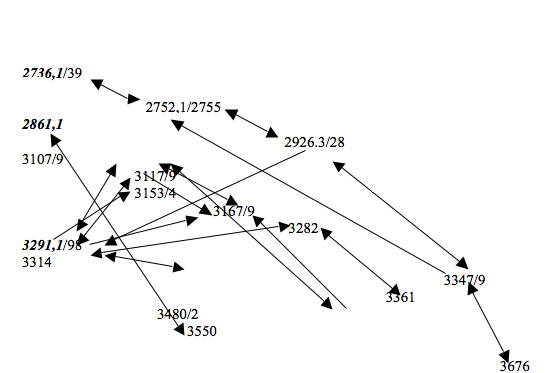

I believe this model is better suited to represent Leopardi’s Zibaldone. The complexity of Leopardi’s notebook was not shared by the other zibaldoni of his time which were mostly used to store all manner of thoughts, literary references, private and philosophical meditations, quotations, a bit of everything like Leopardi’s Zibaldone, but nothing which could be compared with the self-nourishing body of Leopardi’s meditations. But if Leopardi’s Zibaldone has much more to offer than the other zibaldoni, nevertheless it shares with them the primal function of helping not to forget. The internal cross references of the Zibaldone link thoughts written at different intervals of days, weeks, months, even years. The following map which represents some of these references is meant to show the way Leopardi’s thought moves forward and returns in constant interaction with past writing. The map presents on the vertical line a sample of three thoughts drawn from the entry on vitality and sensibility in the index (Indice del mio Zibaldone di pensieri) completed by Leopardi in 1827.

Partial map of the entry Vitalità, Sensibilità. Il grado dell’amor proprio e dell’infelicità del vivente, è in proporzione di esse (from Zib. 2736,1 to Zib. 3291,1) in the Indice del mio Zibaldone di Pensieri and of the internal references.3

The index was an attempt to organize his meditations in a coherent linear system which was supposed to help Leopardi navigate his increasingly chaotic work. However, the map clearly shows that a linear structure could not sufficiently capture the complexity and interconnectedness of Leopardi’s ideas and that the thoughts selected for the index are merely the tip of the iceberg. The internal cross references which can be seen in the map register Leopardi’s turning of the pages, his habit of keeping present in the mind what he has already written, in a continuous dialogue between his thoughts. In a way we could say that they manifest Leopardi’s attitude as an observer of his own writing, and we have seen before that the point of view of the observer modifies or applies different perspectives on the object of observation, which is, in this case, writing itself. A reader of the Zibaldone knows that Leopardi, like Funes, is clearly driven by an almost obsessive need to divide all the thoughts in different parts and to repeat the same concepts page after page. But the practice of reading and writing provides him with a constant opportunity to monitor his own remembering. Like Borges,Leopardiis aware that in order to remember it is necessary to sacrifice details for the sake of more general connections, and that the fractures necessarily need to be smoothed out in a process of becoming. Internal cross references in the Zibaldone have a similar function of tracing a becoming, of connecting two poles of a certain meditation which are inserted in different pages and in different speculative contexts which, as the rhizomatic principle prescribes, change the original nature of the thought.

I would like to conclude by reflecting on how the highlighted meditations on time and the dynamics of writing in the Zibaldone can be assimilated to one of the most significant dynamic processes in Leopardi’s philosophical thought: the flight of the bird. For Leopardi birds inhabit the open space and their distinguishing feature is to be able to cross vast distances, to experience a multitude of sights and surroundings. In a passage from Buffon’s Natural History of the Birds, which is a source for Leopardi’s Praise of the Birds, we find the following description of the flight of the bird which reflects the rhizomatic features I have previously cited:.

Le sensorium de l’oiseau est principalement rempli d’images produites par le sens de la vue; […] ces images sont superficielles, mais très-étendues, & la plupart relatives au mouvement, aux distances, aux espaces; [...] voyant une province entière aussi aisément que nous voyons notre horizon, il porte dans son cerveau une carte géographique des lieux qu’il a vus; que la facilité qu’il a de les parcourir de nouveau, est l’une des causes déterminantes de ses fréquentes promenades & de ses migrations (Buffon, 1770: 58).

[The sensorium (sensitive apparatus) of birds is mostly filled by the images of the eye; these images are superficial but extremely extensive, and mostly related to movement, distances, spaces: while seeing a whole region as easily as we see our horizon, their sensorium produces in their brain a geographical map of the places they have seen. [...] the ease with which they survey these places again and again is one of the reasons for their frequent flights and migrations.]

Referring to the passage above, Sabine Verhulst (1997: 141-142) observes that the text suggests an image of birds as symbols of remembering, as beings made of memory and habituation, whose flight continuously reproduces a primitive trajectory. But the faculty of habituation does not overwhelm their natural impulse towards the unknown. Indeed,

Gli uccelli […] pochissimo soprastanno in un medesimo luogo […] e talvolta, andati a diporto più centinaia di miglia dal paese dove sogliono praticare, il dì medesimo in sul vespro vi si riducono. Anche nel piccolo tempo che soprasseggono in un luogo, tu non li vedi stare mai fermi della persona (PP, ii: 158).

[Birds [...] remain in the same place for a very short while [...] and sometimes they enjoy flying hundreds of miles from the area where they usually stay and then they return there the evening of the same day. Even during the short time they stay in one place, you will never see them sit still (Cecchetti, 1982: 365)].

The same can be said of the writing of the Zibaldone, where habit plays an important but not restrictive role and where the internal cross references do not follow a linear development but take different intersecting routes. Indeed, a very important feature which connects the Zibaldone and the flight of the bird is the relationship between space and time. Because of their ability to fly birds inhabit a plural world dominated by variety. For Leopardi, they are a symbol of the intensity of life, which is to say that they are free from boredom and from the feeling of their own existence. This also means that because they are constantly distracted by external impulses, they are not exposed to the regular pulse of time. Like the lines of flight of the rhizome, and the internal cross references of the Zibaldone, their essence is the becoming which overcomes the fracture.

I believe that the dynamics of constructing and deconstructing the Zibaldone reflects in the first instance Leopardi’s awareness of the problem of divisibility. The resemblance between the internal workings of the Zibaldone and the rhizomatic characteristics of the bird’s flight, and the fact that the bird is a model of a non-linear conception of time and space, make me think that the Zibaldone also attempts to overcome the problem of linearity and divisibility in the performance of writing and reading, and that it does so also through recourse to forgetting, which allows the mind to escape from single fragmentary details and to produce new thinking. When a pair or group of thoughts are joined in a referential process, a new system of correspondences is created, and this is an alternative to the one based on the linearity and sequenciality of the thoughts in between. In the same way as Borges creates the model of forking time to overcome the implications of spatial and temporal freezing induced by temporal fragmentation as examplified by Funes, Leopardi finds a way out of his obsessive practice of surgical investigation by creating a virtual dimension for his thoughts as an alternative to linear progression. But just as the line and the labyrinth will always coexist in Borges’ model, so the process of remoulding of the Zibaldone is neverending and no total synthesis is ever achieved, but only partial syntheses which are often formed only to be deconstructed once again further on.

1 My reference text for Borges is Funes the Memorious (1962: 107-115), abbr. FM. All other works by Borges are from the Penguin edition indicated in the bibliography, and abbr. TL. The edition of the Zibaldone to which I refer is the critical edition by Giuseppe Pacella. All the translations from the Zibaldone (abbr. Zib and followed by the page number in the manuscript) are my own. Other works by Leopardi are cited from the Mondadori edition by Damiani and Rigoni, abbr. PP, followed by volume and page numbers.

2 Cfr. Zib. 1635-36.

3 The numbers in bold, on the vertical line on the left, represent the thoughts of the entry examined. They follow Leopardi’s annotation in the Indice del mio Zibaldone di pensieri (number of the page and paragraph of the manuscript). The other numbers represent the page and paragraph of the internal references with which the thoughts of the Indice are connected. As for the arrows, I have followed the model by Marco Riccini (2000: 86): «le […] frecce a due punte servono a congiungere coppie di pensieri collegati da rimandi “reciproci”, ossia mutuamente connessi e rispondentesi. Le frecce a una sola punta, invece, indicano rimandi che si potranno denominare “univoci”: vale a dire, rimandi da un pensiero all’altro, ai quali non corrisponde, nel pensiero di destinazione, un rimando reciproco al pensiero di origine» [the double-headed arrows represent pairs of thoughts which refer to each other. Single-headed arrows represent single unreciprocated references]. My own translation.

Bibliography

Borges, Jorge Luis, Ficciones, ed. Anthony Kerrigan, New York, Grove Press, 1962.

Borges, Jorge Luis, The Total Library, London, Penguin, 1999.

Buffon, Georges, Louis Leclerc, Discours sur la nature des Oiseaux. Histoire naturelle, Paris, Imprimerie royale, 1770, vol. I.

Egginton, William «Three Versions of Divisibility: Borges, Kant and the Quantum», William Egginton and David E. Johnson (eds), Thinking with Borges (pp. 49-68), Aurora, CO, The Davies Group Publishers, 2009.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, Mille Plateaux (1980) trans. A thousand plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, London, Athlone Press, 1996.

Leopardi, Giacomo, Poesie e prose, Rolando Damiani and Mario Andrea Rigoni (eds), 2 vols., Milan, Mondadori, 1988.

Leopardi, Giacomo Operette Morali, ed. G. Cecchetti, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1982.

Leopardi, Giacomo, Zibaldone, critical edition by Giuseppe Pacella, Milan, Garzanti 1991.

Martin-Jones, David, Deleuze, cinema and national identity: narrative time in national contexts, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2006.

Riccini, Marco, «Lo “Zibaldone di Pensieri”: progettualità e organizzazione del testo», Michael Caesar and Franco D’Intino (eds), Leopardi e il libro nell’età romatica (pp. 81-104). Rome, Bulzoni, 2000.

Verhulst, Sabine, «Buffon, l’Elogio degli uccelli e le figure dell’immaginazione in Leopardi», Studi e problemi di critica testuale, (54), 1997:135-153.